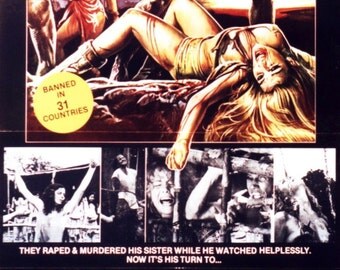

This irony was apparently lost on the BBFC, as the film was not released uncut in the U.K. Overreacting to what he sees as the decay of the day, he picks up a drill and gets to bloody work, becoming a more immediate danger to the public than any of the institutions or epidemics he’d feared. What makes The Driller Killer a particularly ironic victim of the video nasties craze-and it was reportedly a key film in that period, pushing Parliament toward the Video Recordings Act-is that its main character (played by Ferrara) experiences psychosis brought on by his contempt for the seediness of 1970s New York. Rough around the edges and subversive in its slapdash mixture of exploitation and black comedy, The Driller Killer works drug addiction, Catholic guilt, economic despair and moral deterioration into its story of a struggling artist’s descent into madness. 45 and Bad Lieutenant) can be seen as a skeleton key to the rest of the New York gutter poet’s filmography. This scuzzy second effort from Abel Ferrara (and first non-pornographic one, after the gloriously titled 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy) ran afoul of censors almost entirely on the basis of its explicitly violent cover, which depicted a man being drilled through the forehead by the killer and included the perhaps overly descriptive tagline: “As the drill finds its victim…the blood runs in rivers…and the drill keeps tearing through flesh and bone.” But far from an emptily excessive gorefest, Ferrara’s film (predating his better-known provocations like Ms. With Censor out this week, here are ten of those originally listed films that are currently streaming for those interested in adding some color and controversy to their horror-history knowledge. In full, 72 titles were branded as “video nasties,” though only 39 of those titles were successfully prosecuted. or Italy, but titles ran the gamut from stomach-churning exploitation (1977’s Gestapo’s Last Orgy and The Beast in Heat both belonged to the ill-advised but short-lived Naziploitation subgenre) to surprisingly artistic, high-brow explorations of taboo topics like trauma and childhood abuse (Matt Cimber’s The Witch Who Came from the Sea, for example, is now streaming on the Criterion Channel). What were the video nasties? Typically, the films were low-budget horror fare from either the U.S. But when Enid screens a new exploitation title by an enigmatic director, some scenes bear a shocking resemblance to her own formative trauma, leading her down a psychological rabbit hole as she begins to explore long-repressed childhood memories and the more frightening realities they conceal.īut for those diving into this peculiar era of British film history for the first time in real life, an introduction might be in order. Meticulously noting where filmmakers must chop and change their nasties in order to be passed, she sees censorship as a matter of protecting the public health. Censor, set in 1985, centers on a film censor named Enid (Niamh Algar), who screens the most violent and depraved horror flicks ‘80s Britain has to offer.

In 1984, fittingly enough, this era intensified with Parliament’s passage of the Video Recordings Act, which expanded the BBFC’s jurisdiction to include all home video releases. Following a campaign by various members of the press, social commentariat and religious organizations (including the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association, led by influential activist Mary Whitehouse), the then-director of public prosecutions released a list of “video nasties” deemed in violation of obscenity laws, and police began the process of seizing tapes and prosecuting those involved in distributing them. Due to a loophole in film classification laws, these films had been permitted to bypass a typical review process by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), and moral panic set in as authorities questioned what exposure to such explicit content would do to the general public.

With video cassettes newly popular in the early ‘80s, luridly disreputable horror titles took advantage of the U.K.’s then-unregulated home video market, pushing boundaries with their extreme and often sexualized violence.

In Prano Bailey-Bond’s feature debut Censor, out today, the Welsh filmmaker looks back at the notorious Video Nasty Era of British censorship, a fascinating and understudied chapter in recent film history.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)